When string theory meets machine learning

Published:

In my physics master’s thesis, titled Holographic RG flows in gauged supergravity, I studied applications of the AdS/CFT correspondence, which originates from string theory. To tackle the issues I encountered, I have designed and developed a new numerical algorithm, inspired by machine learning.

Overview

In this post, I start off by giving a broad introduction to the research of my thesis, aimed to be understandable for people with a background in physics. Later on, I dig deeper into the so-called principle of holography, also known as AdS/CFT, which is currently one of the most exciting topics in high-energy theoretical physics. I introduce one possible application of holography, namely holographic RG flows, which I studied in my thesis. At the end, I discuss a new algorithm which I developed during my research. This algorithm allowed me to find new (i.e., not reported before in the literature) flow solutions using holography. While string-theoretical details about the context of this algorithm are limited to an absolute minimum, interested readers with the appropriate background are directed towards the full text of the thesis (see below) for more information. The new algorithm constructed in this thesis, inspired by machine learning, is applicable in other circumstances, completely unrelated to string theory, as well. Moreover, it stimulates us to further explore the intersection between (theoretical) physics and machine learning.

The full text of my master thesis can be found here, while my presentation on my work for a broad audience (with a physics background) can be found here.

Introduction: what is string theory?

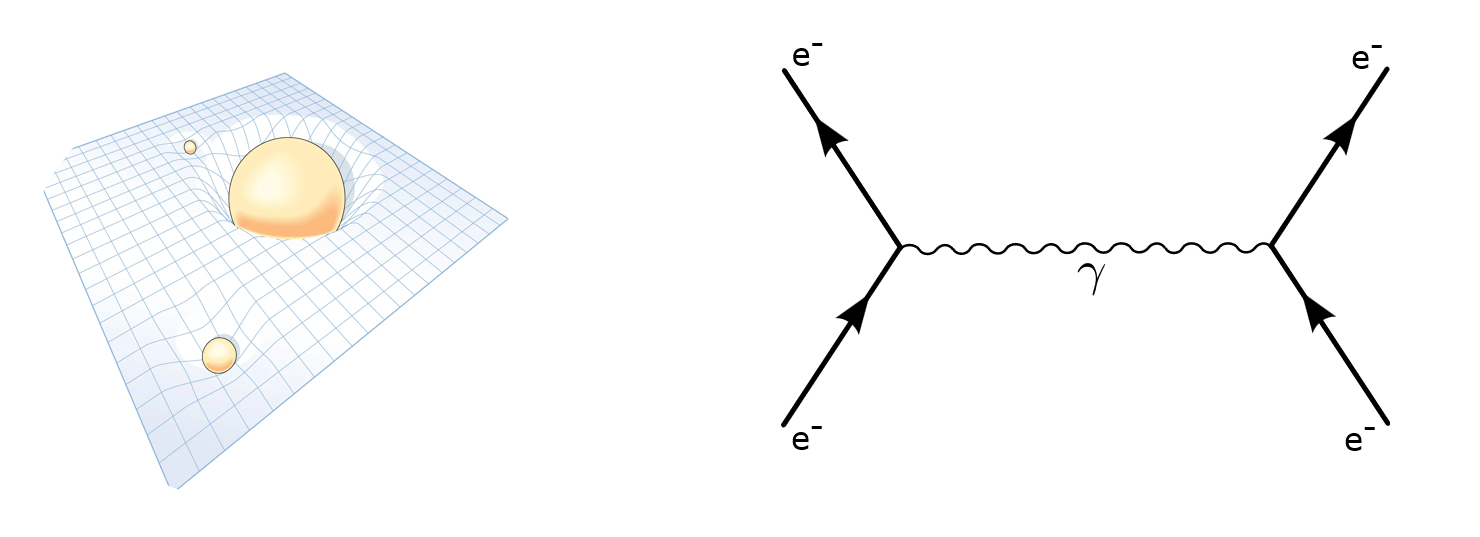

Physics has come a long way since Newton first pondered the equations governing the gravitational attraction of the Earth, the Moon, and all the planets in our solar system. Nowadays, theories in physics are generally divided into two groups of frameworks, and each has been successful so far in their own respective regime. On the one hand, Newton’s theory of gravity as a ‘force’ has been superseded by a much more elegant, mathematically more concise, and an experimentally well-established theory. This new theory is the famous theory of general relativity by Albert Einstein. On the other hand, experiments from the early twentieth century resulted in the discovery of atoms, nuclei, electrons, and a whole zoo of particles living at the smallest of scales we can probe today. The dynamics of Nature at these unimaginable small scales is not deterministic, but rather, predictions involve probabilities. This is the so-called quantum aspect of Nature, which emerges as we zoom into matter, up until the smallest scale we know of today. Quantum mechanics has been refined into quantum field theory (QFT): a framework which combines this quantum aspect of Nature with the idea of fields permeating all of space-time. The Standard Model, the most successful explanation of particle physics to date, is a well-known example of such a QFT.

While both general relativity and QFT are accurate descriptions of Nature, both are only valid in their own ‘regime’. That is, general relativity is an adequate description of Nature at the largest scales, such as planets, stars, galaxies,… On the other hand, the Standard Model reigns at the smallest of scales, determining the dynamics of the lightest of particles we know. Both account for different forces of Nature. General relativity is a theory of gravity, while the Standard Model accounts for the three other fundamental interactions: the electromagnetic, weak and strong force. In a QFT, these interactions are modelled through the exchange of force-carrying particles, known as gauge bosons. As such, the Standard Model is said to be a gauge theory.

A sad truth that we must face is that, so far, physicsts have been unable to unify general relativity with the framework of QFT. When we naively try to “quantize gravity”, meaning that we model the gravitational force using a force carrier (a boson), the QFT calculations yield infinities which render this quantum theory ‘sick’ (unrenormalizable). In short: such a theory has no predictive power, and clearly does not belong to the realm of physics. However, some situations require such a unified framework, known as quantum gravity, in order to make sense of Nature. Indeed, examples include black holes or the Big Bang.

During my thesis, I performed independent research at the high-energy group of the ITF, the Institute for Theoretical Physics at KU Leuven, under the supervision of my promotor Nikolay Bobev. Nikolay’s research, like many other theoretical physicists around the globe, deals with string theory. As of now, string theory is the only known consistent theory of quantum gravity, although the mathematics become so complicated that we still have to figure out how to fit our own universe into the theory consistently. Nevertheless, a lot of research is dedicated towards understanding string theory and its implications. The basic premise of string theory is that all known fundamental point-like particles are in fact not point-like. That is, if you could zoom in all the way down to the Planck scale, string theory postulates that each fundamental particle is in fact a single tiny string. Thus, the point particles get smeared out into one-dimensional, spatially extended objects, the strings.

If point particles become strings, where did the conventional particles go? How can we recover an electron from the strings? To resolve this, in string theory, the different vibrational modes of the string are interpreted to give rise to different particles. With a bit of imagination, we can therefore state that string theory renders the universe into one musical magnum opus, each note played by a particle.

A brief introduction to holography (or AdS/CFT)

One of the results that came out of studies of string theory is a remarkable duality. A duality in this context is an equivalence between (a priori) seemingly different theories. Dualities are powerful tools in physics, as demonstrated by a wide range of dualities which mark the history of physics. Well-known examples are the wave/particle duality from quantum mechanics, the electric/magnetic duality (generalized to the Montonen-Olive duality for non-abelian gauge theories) and the Kramers-Wannier duality from statistical physics. Note, however, that all these dualities are formulated within the same framework, i.e. inside quantum mechanics, inside a certain QFT,…

Often, the correspondence between theories is made manifest by changing the value of a coupling constant in the theory. For example, a strong/weak duality provides a correspondence between a theory with coupling constant $g$ to a similar theory, but with coupling constant $1/g$. Thus, if $g$ is large, which we call strong coupling, the ‘dual theory’ has a small coupling $1/g$ and is said to be weakly coupled. One example is the Kramers-Wannier duality, which provides a link between the free energy of the 2D Ising model at a low temperature to another Ising model at high temperature. The term ‘strongly coupled’ implies that perturbation expansions (visualized by the famous Feynman diagrams) will diverge, and calculations become extremely difficult or even impossible. Clearly, a strong/weak duality would simplify our lives, as it allows us to translate a difficult, strongly coupled theory into a “simpler” (that is, weakly coupled) theory. The duality allows us to bridge into a different theory, and perform the calculations in a simpler environment.

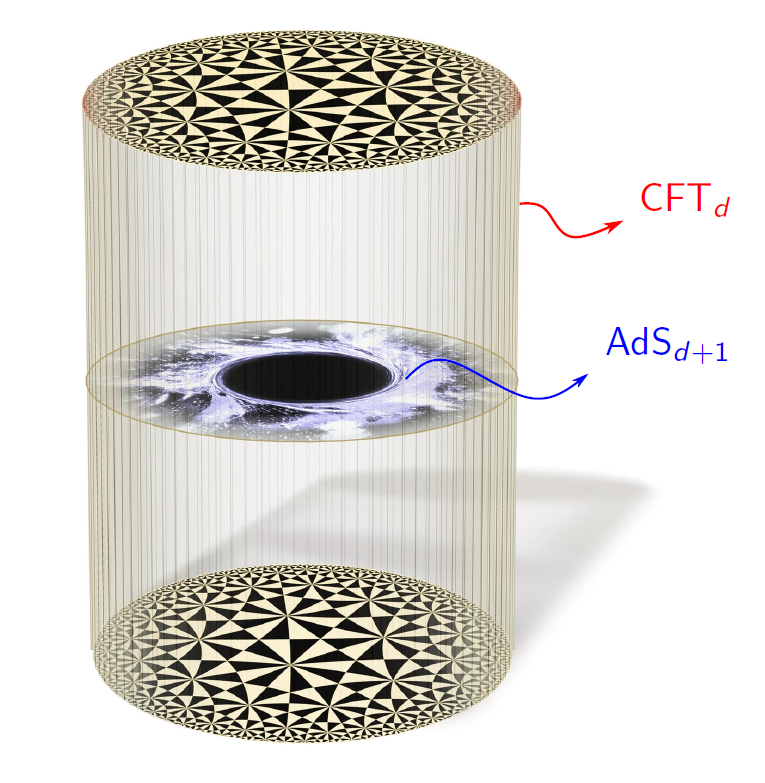

Back to string theory. As mentioned, a remarkable duality was discovered which turned out to provide completely new insights into the nature of quantum gravity. I say that this duality is remarkable, since, unlike the dualities mentioned above, it provides a link between two completely different frameworks. On one side of the duality, we have a theory of gravity (which is called the “AdS” side of the correspondence, named after an AdS space-time). On the other side of the correspondence lies a gauge quantum field theory (often labeled “CFT”, for reasons beyond the scope of this post). These are precisely the two celebrated frameworks of physics, which are (as of today) irreconcilable with each other!

This duality is often called the AdS/CFT correspondence (or less frequently gravity/gauge correspondence), but one also encounters the term holography. The reason is that the two theories live in a different number of dimensions of space-time, making the duality even more remarkable. That is, if the gauge quantum field theory is formulated in $d$ dimensions, the gravity theory is formulated in $d+1$ dimensions. As such, the analogy is often made that the gravity theory (the “AdS”) is a certain 3D volume which can be interpreted as the projection of some 2D screen, which is the “CFT”: a set-up which resembles a hologram. What’s even more exciting is the fact that AdS/CFT is an example of a strong/weak duality, as explained above. That is, whenever one of the sides of the correspondence is strongly coupled, its “dual theory” is weakly coupled. Naturally, one starts to wonder about what applications this may harbor. In my thesis, I considered one specific application, namely RG flows.

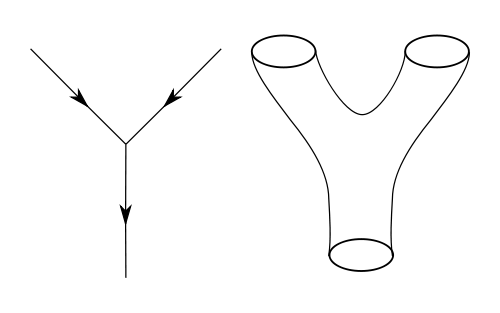

RG flows, and their holographic translation

One of the most important realizations of studies of quantum field theory is that physics depends on energy. That is, the strength of an interaction depends on the distance separation (or equivalently, the energy scale) at which the interaction is being probed. While the details go beyond the scope of this post, it suffices to know that in a QFT, we often “integrate out” the contributions coming from (unknown) physics at higher energies. Here ‘higher’ means above a certain cut-off energy scale $\mu$ that we introduce ourselves artificially. This way, we make the QFT dependent on this cut-off energy scale $\mu$. As it turns out, a variation of this scale $\mu$ induces a variation in the strength of the interaction, $g$. In short, $g$ becomes a function of the parameter $\mu$, and we would like to determine the behaviour $g(\mu)$ for a theory. It turns out that the equations governing the evolution of $g(\mu)$ constitute a dynamical system. That is, they are first-order ordinary differential equations, or more simply stated: gradient flow equations. Here, ‘flow’ is interpreted with the evolution parameter being energy rather than time. Solutions to this dynamical system are called RG flows, and tell us how our QFT changes as we change the energy scale $\mu$.

However, RG flows are nearly impossible to compute in practice if the theory is strongly coupled, which is often the case for quantum field theories encountered in the context of string theory. Luckily, the solution to this problem is provided by string theory itself! Indeed, one can make calculations tractable by relying on the AdS/CFT correspondence. By using holography, one can translate a strongly coupled QFT into the language of a weakly coupled gravity theory, in which the RG flows can be computed. The gravity solutions that are ‘dual to’ the RG flows in the QFT are called holographic RG flows. These are precisely the topic of my thesis.

My goal is to compute new holographic RG flow solutions in specific cases of QFTs which are related to string theory, where the dual gravity theory is known as a gauged supergravity. Further details are given in the full text of the thesis.

The goal, boiled down to its essence

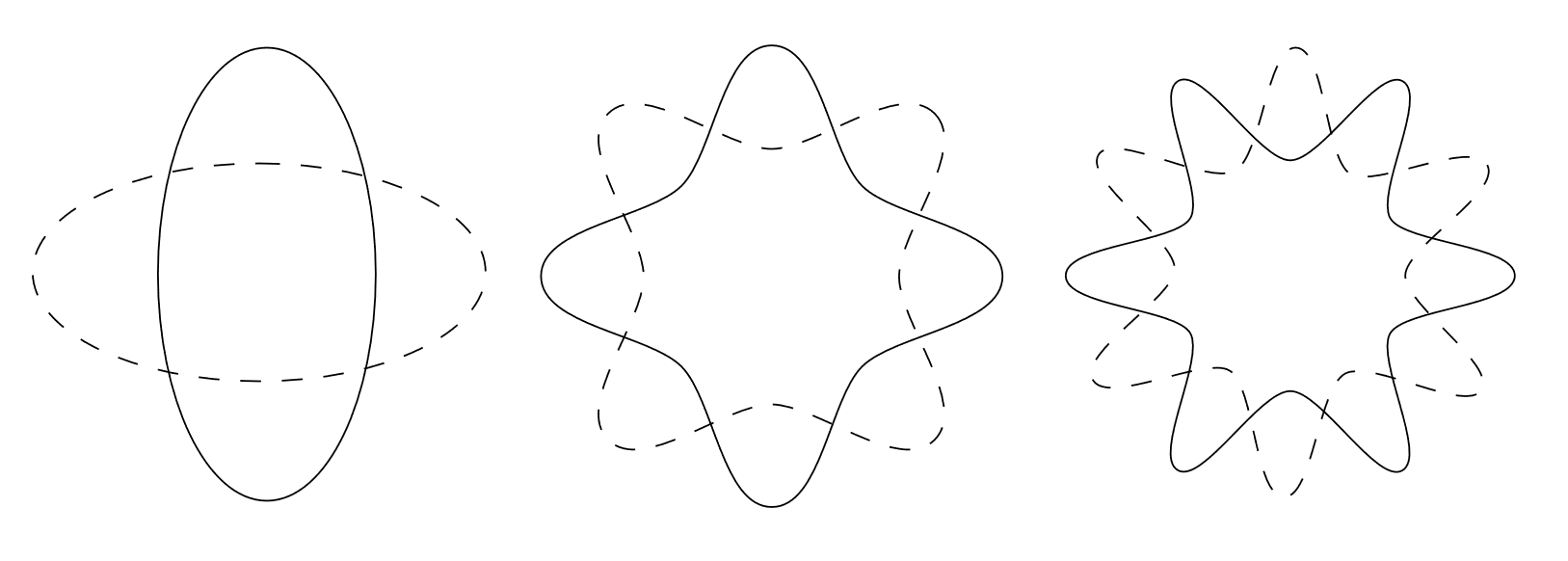

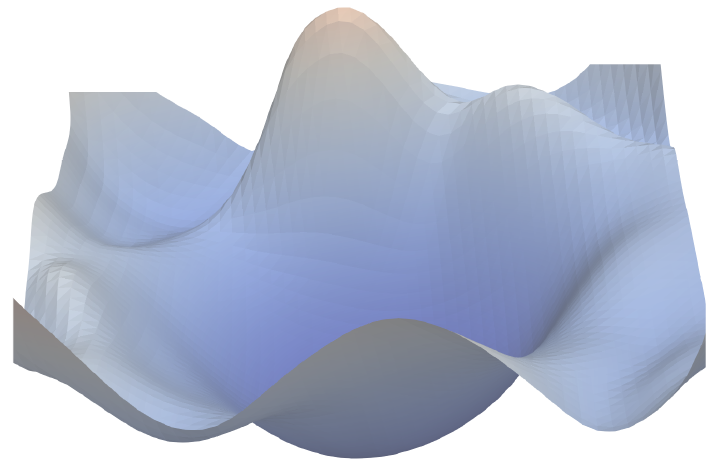

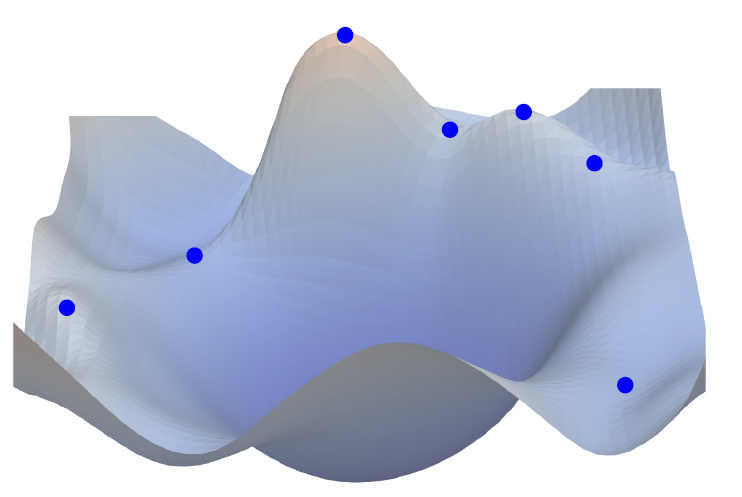

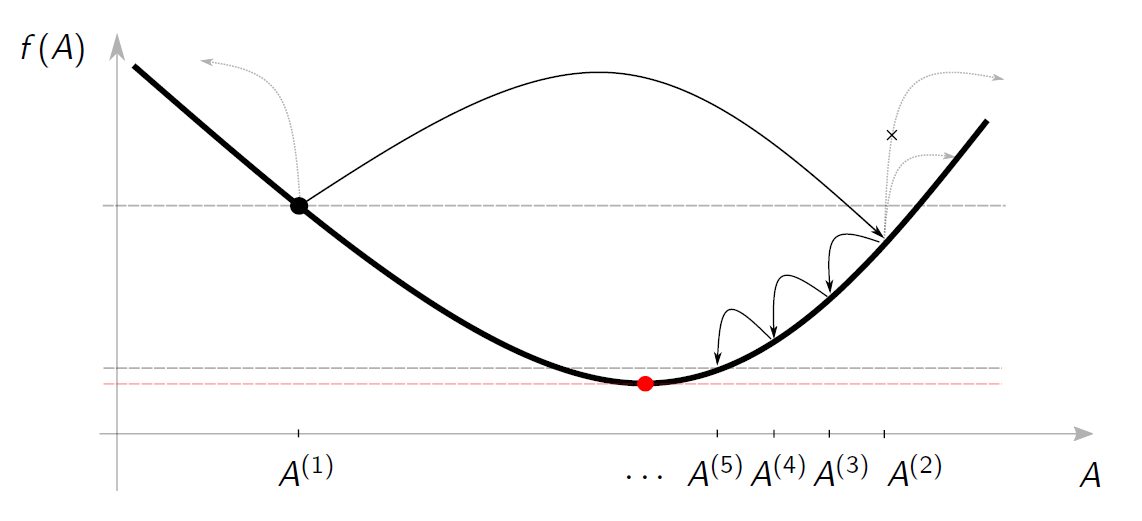

Dropping all terminology of string theory, the goal is actually pretty simple. The flow solutions that we want to find are simply an excursion through a certain landscape corresponding to the scalar potential of the theory of interest. This scalar potential is drawn, schematically, in the image below.

We start from an initial position on a ‘peak’ of this landscape, which is an extremum of this scalar potential. That is, if we imagine a ball sitting at this location, it will remain here if left unbothered. More precisely, the extrema of the scalar potential give steady-state solutions of space-times, which are empty AdS space-times. They are denoted by blue dots in the figure below.

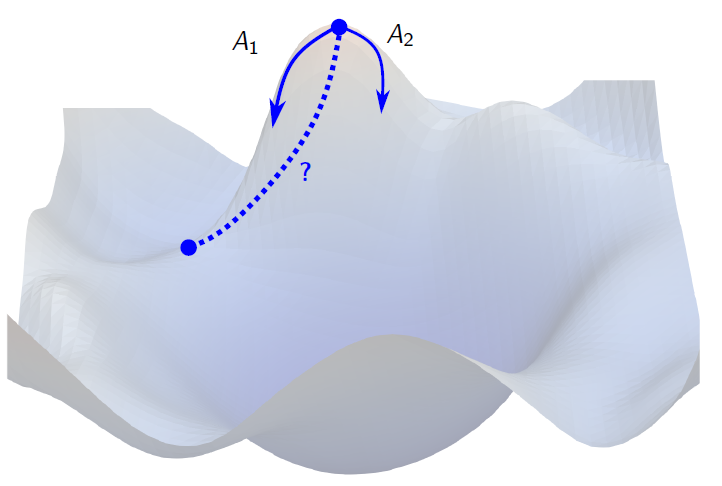

When we give a kick to the fictitious ball lying at one extremum, however, it starts rolling down the potential landscape. In our case, this dynamics is governed by a certain set of complicated equations of motion which come out of string theory. The important part is that this system of equations is a dynamical system, i.e. a set of gradient flow equations. Hence, the motion of the ball is a flow solution. Our goal is to find the correct kick to give to the ball in order that the flow will end up in another steady-state solution, where the ball settles into another extremum of the scalar potential. These flow solutions are the holographic RG flows we wish to find.

Bringing in some of the string theory details, the scalar potential is a function of 70(!) scalar fields, which can vary along the flow. While this clearly makes the equations too complicated to solve, even numerically, research done in the past was able to find certain flow solutions involving only a subset of those scalar fields. In particular, my promotor was able to find holographic RG flows involving 6 out of the total of 70 scalar fields. The goal of my thesis was to find new flow solutions by extending the equations to include 14 scalar fields in total.

The problem

The major hurdle that I faced was that research in the past involved a brute force method to find the correct ‘kick’ to induce a flow solution. The idea was very crude: simply give a kick in all possible directions, let the solution flow, and check whether another extremum is reached in the end. However, since I had to work in a larger, 14-dimensional space (rather than 6-dimensional, as in previous papers), this method was far too inefficient and simply inadequate to find the flow solutions. Therefore, I designed and developed my own numerical algorithm which used a more direct search approach instead of the brute force method.

The step descent algorithm

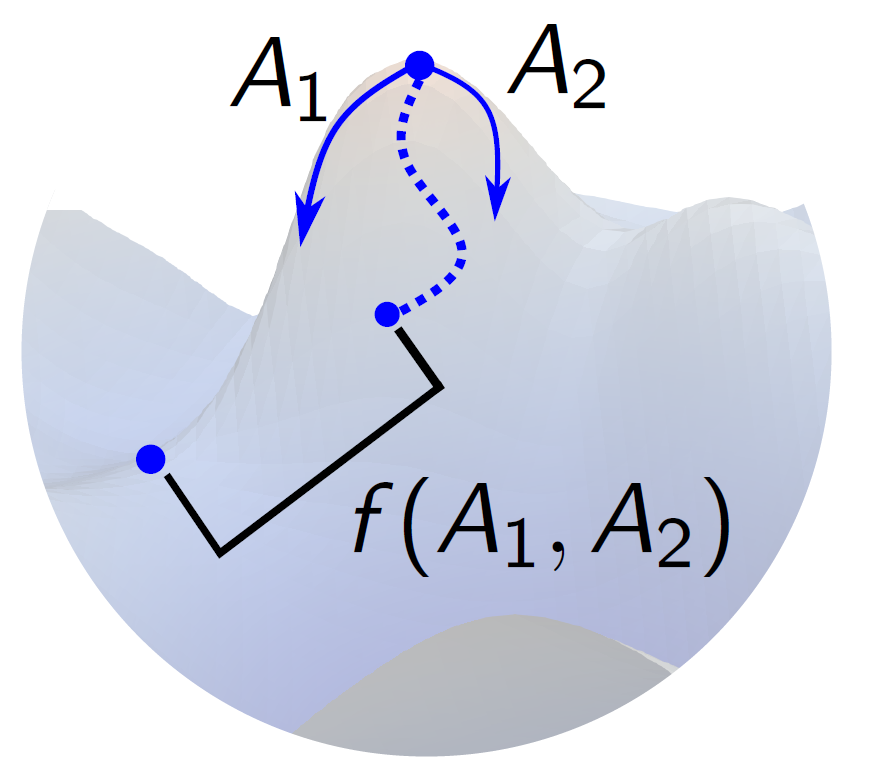

The algorithm that I wrote for the thesis is inspired by machine learning. The core idea behind any machine learning algorithm is the minimization of a certain loss function, which essentially measures the discrepancy between an output of the algorithm and the correct answer or desired output. The loss function depends on a certain number of parameters which influence the output of the algorithm. Importantly, whenever the loss function is differentiable with respect to these parameters, one can iteratively update the parameters along the gradient of the loss function in order to improve the algorithm output. Such so-called gradient descent algorithms are quite popular and well-studied.

In our set-up, the parameters to be fine-tuned are the different ‘kicks’ we can give to the starting position in the potential landscape. For the loss function, I chose the distance between the endpoint of a flow solution constructed from a certain kick and the target extremum that we would like to end in at the end of the flow solution.

To minimize this loss function, a gradient descent was too costly in our set-up. Therefore, a simpler version is constructed which I named the step descent algorithm. Here, each of the parameters of the loss function gets updated by taking discrete steps up and down of variable step size, such that we explore the full parameter space in the direction of decreasing loss function. By continuously iterating over all the parameters of the loss function and updating the parameters in this regard, we aim to minimize the loss function, hopefully reaching a minimum corresponding to a flow solution which interpolates between two different extrema of the scalar potential. Such a solution is then precisely the holographic RG flow we would like to discover.

Results

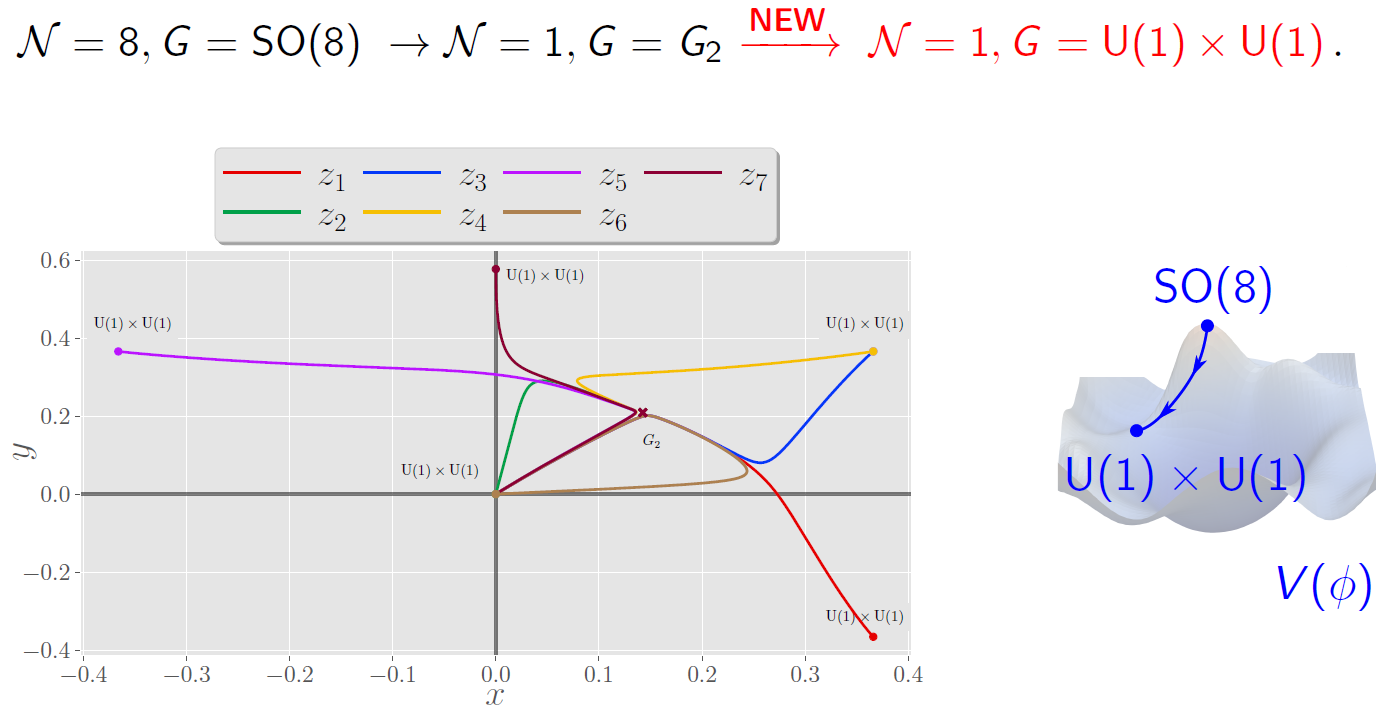

The algorithm was successful, and gave new holographic RG flows in different gauged supergravity theories. An example is shown below. Here, we plot the 14 scalar fields that are allowed to vary along the flow by grouping them into seven complex scalars $z_i$, plotted on top of each other in the complex plane. The extrema of the scalar potential are located at the origin of the plot and at the dots and cross. The labels $\mathcal{N}$ and $G$ above refer to the various amounts of (super)symmetry preserved by the AdS space-time solutions at these extrema of the scalar potential. More details and other new results can be found in the thesis.

Conclusion

In the thesis, I constructed new holographic RG flow solutions in various gauged supergravity theories. These demonstrate the power of AdS/CFT, a new duality which originated from string theory, a consistent yet complicated theory of quantum gravity unifying all interactions in Nature. My work extended previous results and paved the way towards future work through the introduction of a novel numerical algorithm. Moreover, this algorithm can be applied in other areas of physics which involve dynamical systems. As it is inspired by machine learning, future work (without restricting our attention to the specific case of holographic RG flows) may benefit from exploring the intersection of machine learning methods with theoretical or computational physics. Expanding this intersection of knowledge domains is certainly an exciting prospect which may influence the whole body of physics in general.

References

[1] Becker, Katrin, Melanie Becker, and John H. Schwarz. String theory and M-theory: A modern introduction. Cambridge university press, 2006.