Spatiotemporal coordination of the cell division cycle

Published:

In oscillatory media, heterogeneities act as sources of waves which end up synchronizing the whole medium. In biological systems, these waves are a crucial way of transmitting information. At GelensLab, recent experiments increased an interest in spiral wave phenomena in the context of cell cycle oscillations of Xenopus laevis frogs. During my internship, my goal was to gain insight into properties of these wave phenomena through simulations of mathematical models.

Overview

In this post, I provide an introduction to the research performed during my internship, as well as briefly explain the mathematical model that we used for the numerical simulations.

The full report can be found here, while my presentation on my work can be found here.

Introduction

Oscillations are present everywhere in Nature, from the orbits of planets and stars on cosmic scales, to cycles in the divison of cells in biological systems. Organisms rely on travelling wave phenomena and pattern formation to transmit information across large distances in an efficient way. Spiral waves and target wave patterns are particular examples of dynamical pattern formation appearing in complex spatiotemporal systems and have been observed in physical, chemical and biological contexts, such as the famous Belousov-Zhabotinsky reaction.

Travelling waves have been observed before by the team of GelensLab in the Xenopus laevis frog’s cell extracts. Since these waves and patterns play an important role in the coordination of the cell cycle oscillations, a lot of research has been dedicated to understanding these patterns, their properties and their origin through mathematical models which can be studied numerically.

Recently, spiral patterns have been observed the first time in experiments at GelensLab. The spirals appeared together with target patterns in droplets containing extract, which are two-dimensional extended spatial systems.

Motivated by this observation, we would like to model the formation of target patterns and spirals in two-dimensional systems in order to understand their properties, such as speeds of the waves spreading out and the speed by which these patterns entrain the medium, as a function of the model’s parameters and details of the system. Given the observation that target and spiral patterns can appear simultaneously in a system, we also studied the interaction between these patterns, again as a function of parameters underlying the model of the oscillations.

FitzHugh-Nagumo model

Whenever we want to model a complicated, biological system, we necessarily have to make a compromise between simplicity, ensuring that our analysis is tractable and solvable, and complexity that is inherently present in the system due to many biochemical interactions. Here, we employ a system of partial differential equations of two variables $u$ and $v$ which are capable to capture the main behaviour of target and spiral patterns. For our model, we take inspiration from earlier numerical work of the lab, related to travelling waves observed in one-dimensional extracts. To model the cell cycle oscillations, we make use of FitzHugh-Nagumo (FHN) equations related to the well-known Van der Pol oscillator. The equations are \begin{equation} \partial_t u = \varepsilon^{-1} (v - \tfrac14 d u (u^2 - b)) + D_u \nabla^2 u \equiv \varepsilon^{-1} (v - f(u)) + D_u \nabla^2 u \end{equation} \begin{equation} \partial_t v = a - u + D_v \nabla^2 v \end{equation} The FHN equations depend on a number of parameters, which are explained in detail in the report. Most importantly, the parameter $\varepsilon$ is called the timescale separation between the variables $u$ and $v$, and determines the shape of the time series. For low values of, the oscillations are relaxation-like (with sudden, sharp jumps in values), while for high values, the oscillations have sinusoidal waveforms for both variables.

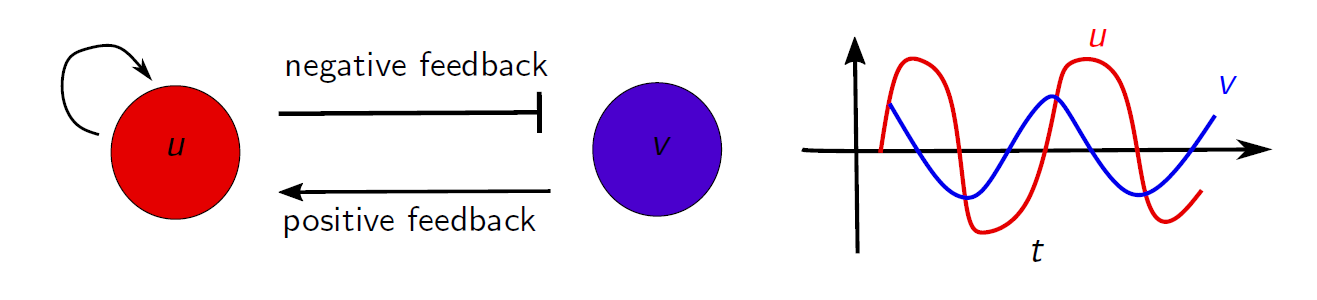

Due to the different nature of the terms, the above equations are called reaction-diffusion equations. The variables $u$ and $v$ represent chemical concentrations or activity which interact with each other, and both are allowed to diffuse in space. Focusing on the reaction part, the interaction is visualized in the diagram below. Since we have a negative feedback loop, the values of $u$ and $v$ will have an oscillatory behaviour as a function of time. This is an essential and desired feature of our model, as we want to be able to model cell cycle oscillations. If we turn off the spatial extent of the system (i.e., ignore the diffusion terms), the time series of $u$ and $v$ will be oscillations, as shown below.

In a spatially extended system, such as the extracts used in the experiments, individual oscillators are coupled to each other through diffusion. Combined with the reaction part of the FHN equations, which produced oscillations, coherent wave patterns can emerge. Hence, by simulating these equations on a computer, we can numerically study the wave patterns observed in the experiments.

Wave patterns

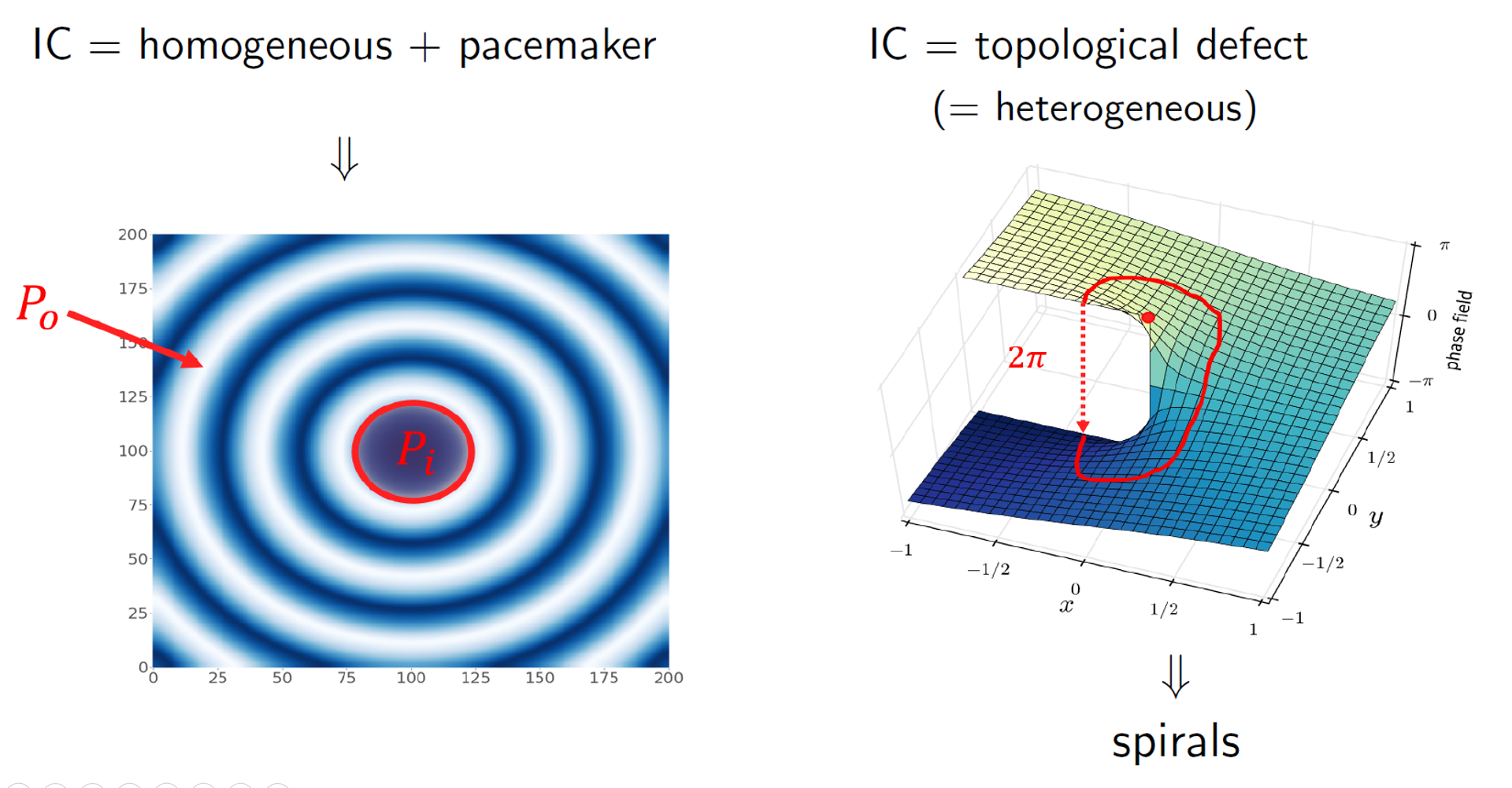

Two competing wave patterns have been observed in experiments. Besides spiral waves, circular waves, called target patterns frequently arise in the cell cycle oscillations. Which kind of pattern emerges out of our simulation depends on the initial condition we start from. In both cases, we put an inhomogeneity in the system:

- Target patterns arise when we put a pacemaker in the system. Pacemakers are regions in space which oscillate faster than their surroundings ($P_i < P_o$).

- Spiral waves arise from a topological defect. These are heterogeneous distributions for $u$ and $v$ which have a singularity in the so-called phase field.

More details on the numerical methods are provided in the report and presentation provided at the beginning of this page. In the remainder of this post, I’ll focus on a few important results coming out of the internship. More results of the study are provided in the report.

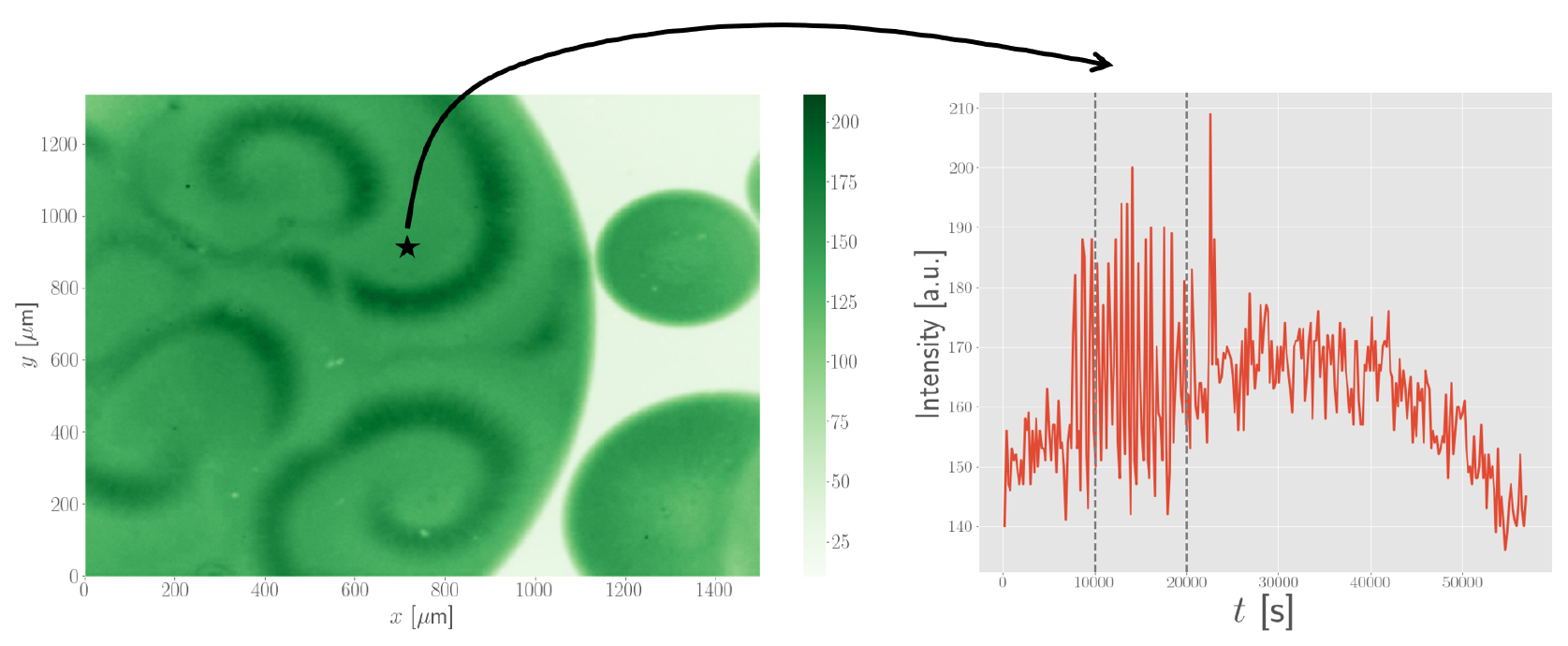

Periods of spiral waves

We first looked at a few properties of the spiral waves as observed in the experiments. After cleaning up some of the data, we computed the periods of the spiral waves that were observed by extracting a time series at different locations in the experimental set-up, as shown below.

Surprisingly, we found that the periods of spiral waves was on the order of 10 to 20 minutes. For comparison, earlier experiments involving target patterns had periods on the order of 40 minutes. It turned out that spiral waves were able to reduce the period of the oscillation.

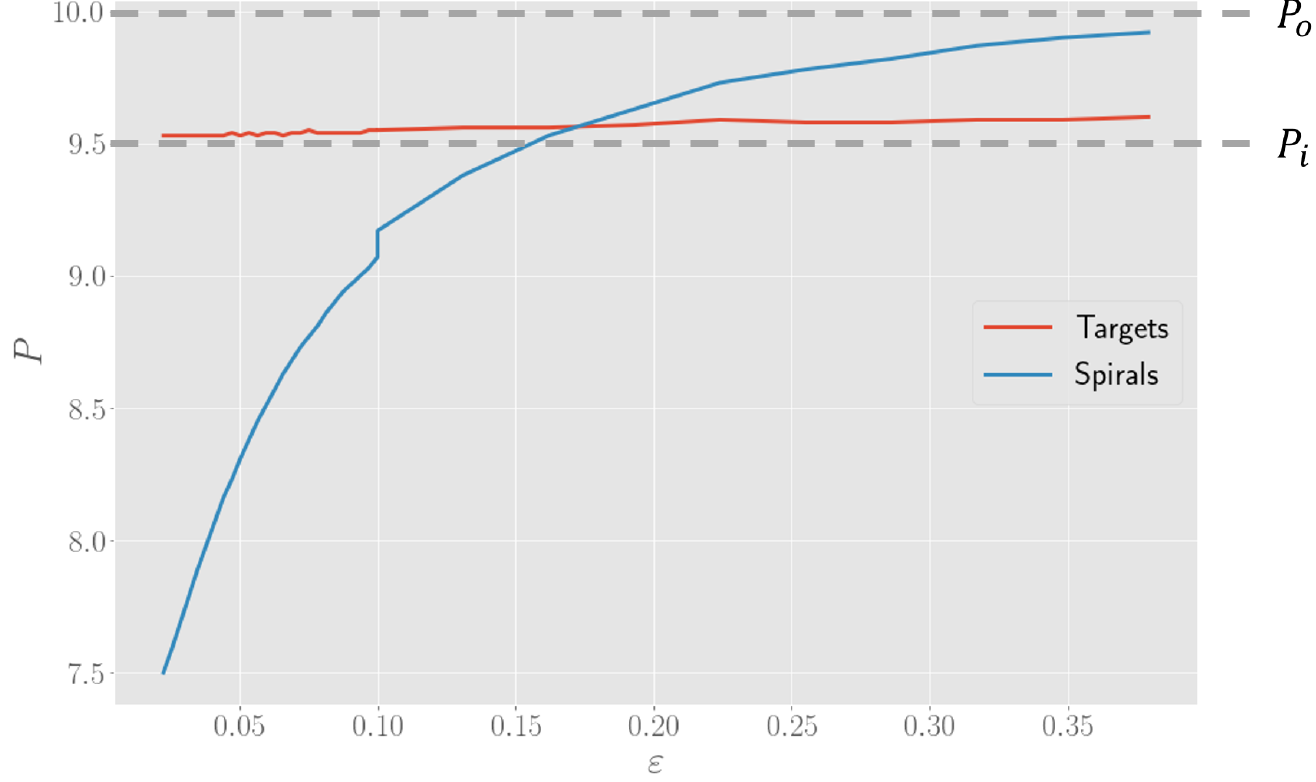

In order to check if the simulations were able to reproduce this result, we varied the parameters of the model and computed the oscillation periods, scanning a large number of values. To make this computationally feasible, we made use of a HPC cluster of supercomputers from the VSC (more info can be found here). As it turns out, simulations show that the period of spirals and target patterns is quite similar for oscillation-like dynamics, whereas spirals are able to produce a much lower period for relaxation-like dynamics, which is controlled by the parameter $\varepsilon$. Target patterns have a nearly constant period, likely due to the presence of a pacemaker region which enforces this period.

Competing wave patterns

In the experiments, it was also observed that target patterns and spiral waves can co-exist, and will compete with each other to take over the medium. In an extreme case, it was even observed that spirals can turn over into target patterns.

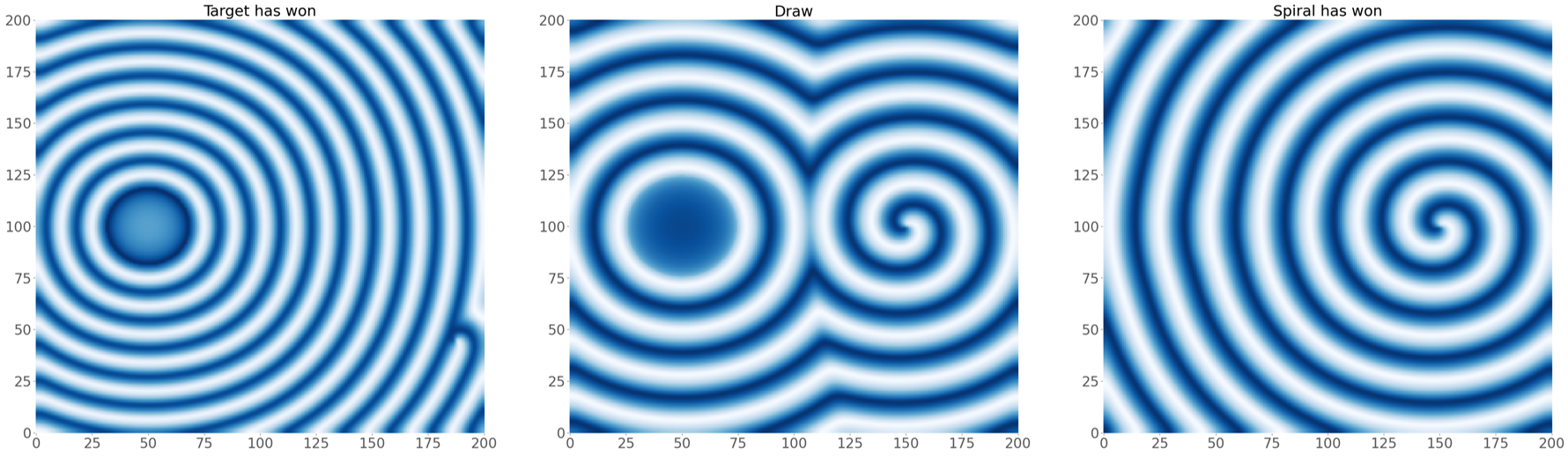

As such, we are interested in modelling the interplay between spiral waves and target patterns with our FHN model. In the internship, we considered an initial condition with a pacemaker region along with a topological defect. Depending on the model parameters, and the properties of the pacemaker region (size $R$ and period difference $h = P_o - P_i$), there are three possible scenarios at the end of a simulation which are shown below.

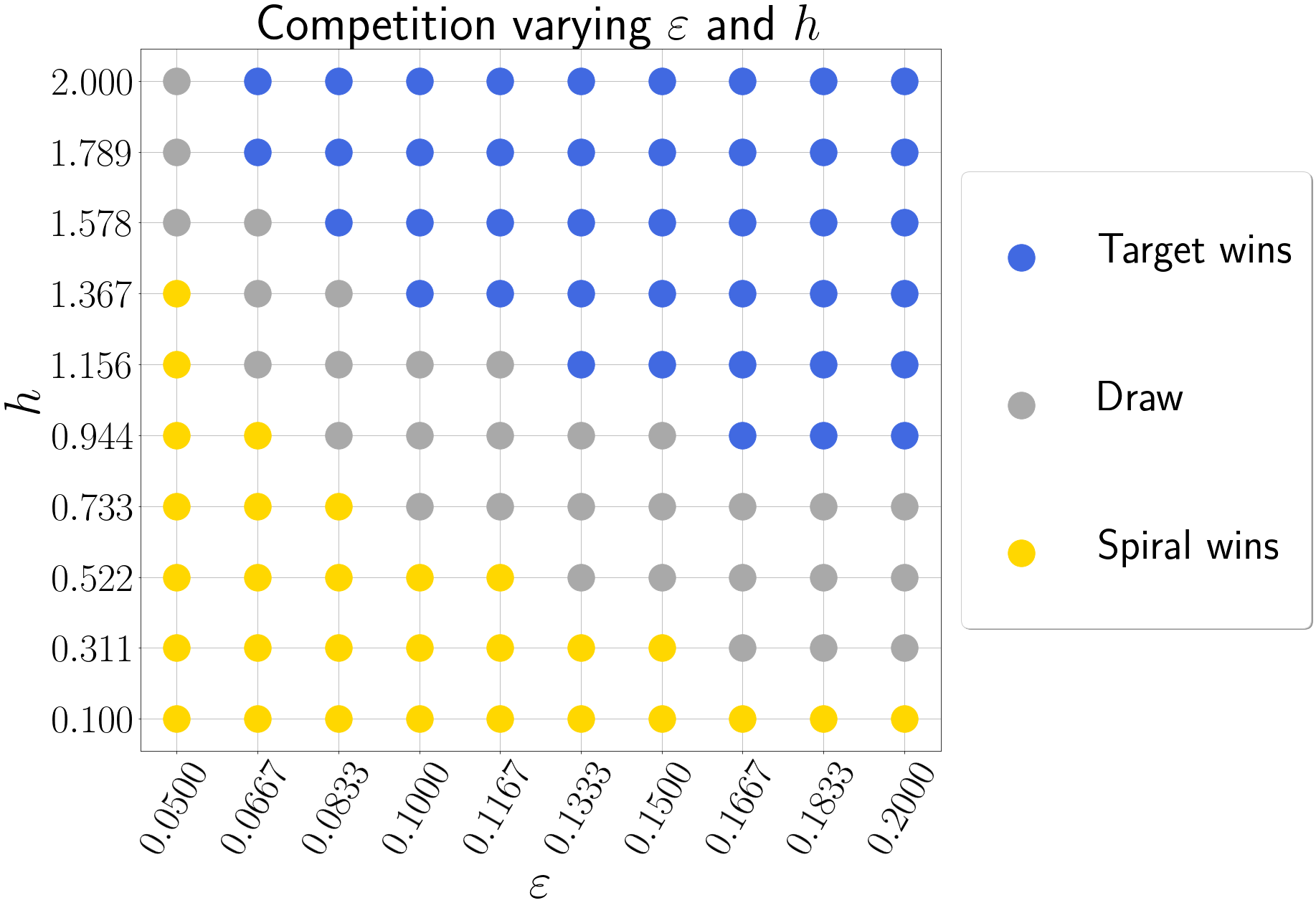

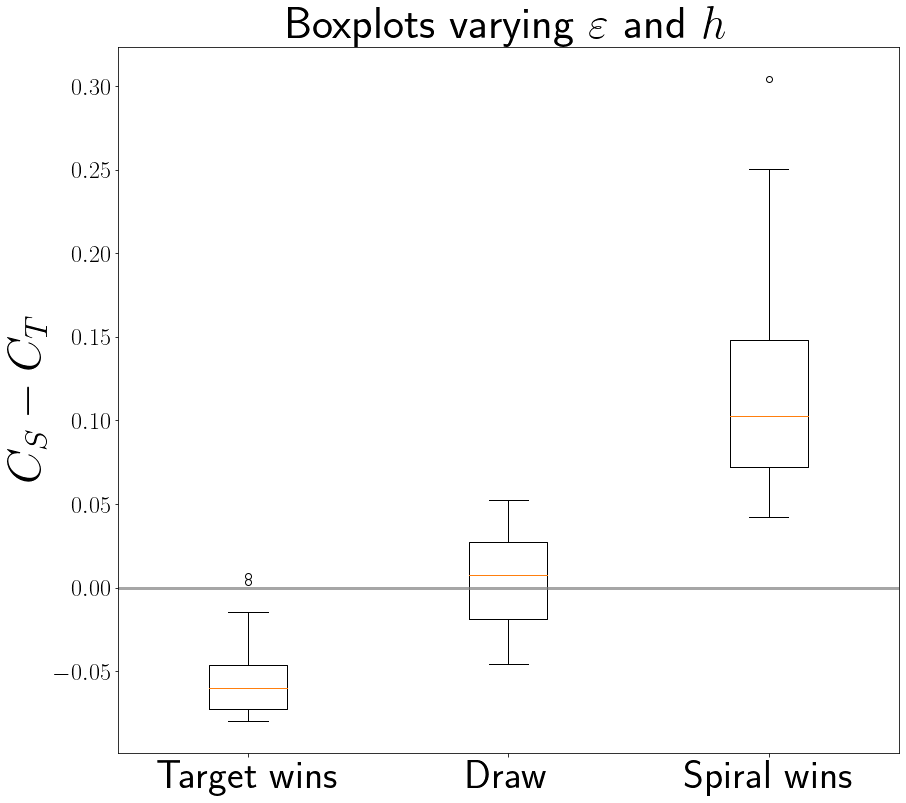

We simulated this set-up for various properties of the initial condition, again by relying on the HPC cluster of supercomputers from VSC. We numerically detected the outcome of the simulations after a large time period such that the system reached a steady state. One survey, where we varied the timescale separation $\varepsilon$ and $h = P_o - P_i$, the period difference of the pacemaker, is shown below.

Grouping these outcomes together, we tried to establish the relevant factor deciding the outcome of the competition. Below, we show the distributions of the envelopespeeds of the spiral and target patterns. The envelopespeed is the speed with which a wave pattern takes over the surrounding medium. The results seem to indicate that there is a strong correlation between the envelopespeed of a pattern and the final outcome of the competition between patterns: a wave pattern with a larger envelopespeed is more likely to overtake the medium. Future work will delve deeper into other possible explanations.

Conclusion

In this internship, I have looked at the properties of spiral waves and target patterns in two-dimensional systems by numerical studies of a FitzHugh-Nagumo model of reaction-diffusion equations. The similarities or differences between how these two patterns behave under variation of the parameters of the system can provide crucial information regarding how biological systems rely on either target patterns or spiral waves (or both) to transmit information within the cytoplasm of a cell. Future work can build on the interaction and relation between the two patterns, and study in detail how the numerical simulations are related to experiments performed in the lab, possibly even inspiring future experimental work in the field. Understanding how waves, originating from pacemaker regions or topological defects, travel around in biological systems is of central importance in understanding how life organizes and coordinates oscillations in basic functions such as divisions in cell cycles. With evolution as driving force and vast amounts of time, lifeforms were able to construct mechanisms that optimize their functioning. Figuring out the properties of different wave patterns appearing in Nature is a crucial step towards understanding why evolution curated these distinct mechanisms to transmit information, eventually adding to our understanding of deeper questions about life in general.